ABSTRACT:

INTRODUCTION:

An individual with acute LGIB classically presents with the sudden onset of hematochezia (maroon or red blood passed per rectum). However, in rare cases, patients with bleeding from the cecum/right colon can present with melena (black, tarry stools) (5). In addition, hematochezia can be seen in patients with brisk upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). Approximately 15% of patients with presumed LGIB are ultimately found to have an upper GI source for their bleeding (6). Historically, LGIB was defined as bleeding from a source distal to the Ligament of Treitz. However, bleeding from the small intestine (middle GI bleeding) is distinct from colonic bleeding in terms of presentation, management, and outcomes (7). For the purposes of this guideline, we define LGIB as the onset of hematochezia originating from either the colon or the rectum (8).

In this practice guideline, we discuss the main goals of management of patients with LGIB. First, we discuss the initial evaluation and management of patients with acute LGIB including hemodynamic resuscitation, risk stratification, and management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents (antithrombotic agents). We then discuss colonoscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool including preparation, timing, and endoscopic hemostasis. Next, we outline non-colonoscopic diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for LGIB. Finally, we discuss prevention of recurrent LGIB and the role of repeat colonoscopy for recurrent bleeding events.

Each section of this document presents key recommendations followed by a summary of supporting evidence. A summary of the key recommendations is presented in Table 1.

With the assistance of a health sciences librarian, a systematic search of the literature was conducted covering the years 1 January 1968 through 2 March 2015 in the PubMed and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The PubMed search used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), as well as terms appearing in titles and abstracts.

The strategy used to cover the lower gastrointestinal tract included (‘Exp Intestine, Large’[Mesh] OR ‘Exp Lower Gastrointestinal Tract’[Mesh] OR lower gastrointestinal[tiab] OR lower intestinal[tiab]). These terms were combined with terms for gastrointestinal bleeding including ‘Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage’[Mesh:noexp] OR rectal bleeding[tiab] OR colonic hemorrhage[tiab] OR colonic hemorrhages[tiab] OR colonic bleeding[tiab] OR hematochezia[tiab] OR haematochezia[tiab] OR rectal bleed[tiab] OR diverticular bleeding[tiab] OR diverticular bleed[tiab] OR diverticular hemorrhage[tiab] OR severe bleeding[tiab]OR active bleeding[tiab] OR melena[tiab] OR acute bleed[tiab] OR acute bleeding[tiab] OR acute haemorrhage[tiab] OR acute haemorrhage[tiab]) OR (LGIB[tiab] OR LIB[tiab]). The final group was limited to English language and human studies. Citations dealing with children and prostatic neoplasms were excluded. The following website will pull up the PubMed search strategy:http://tinyurl.com/ofnxphu.

Search strategies in EMBASE and the Cochrane Library databases replicated the terms, limits, and features used in the PubMed search strategy.

In addition to the literature search, we reviewed the references of identified articles for additional studies. We also performed targeted searches on topics for which there is relevant literature for UGIB but not LGIB including hemodynamic resuscitation/blood product transfusions and management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications.

We used the GRADE system to grade the quality of evidence and rate the strength of each recommendation (9). The quality of evidence, which influences the strength of recommendation, ranges from “high” (further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect) to “moderate” (further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate) to “low” (further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate) and “very low” (any estimate of effect is very uncertain). The strength of a recommendation is graded as strong when the desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects and is graded as conditional when uncertainty exists about the trade-offs (9). Other factors affecting the strength of recommendation include variability in values and preferences of patients and whether an intervention represents a wise use of resources (9). In the GRADE system, randomized trials are considered high-quality evidence but can be downrated depending on the size, quality, and consistency of studies. Observational studies are generally rated as low-quality studies.

Table 1. Summary and strength of recommendations

Evaluation and risk stratification

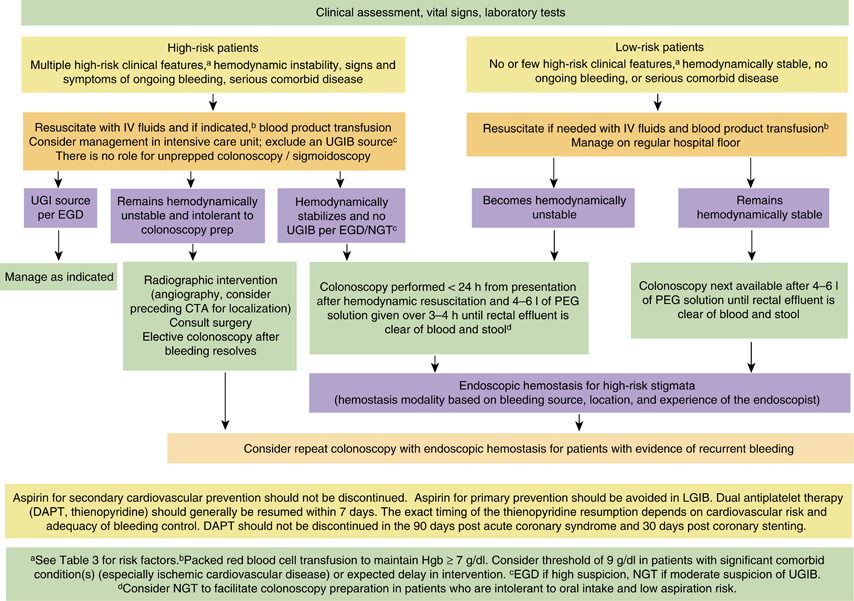

1. A focused history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation should be obtained at the time of patient presentation to assess the severity of bleeding and its possible location and etiology. Initial patient assessment and hemodynamic resuscitation should be performed simultaneously (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

2. Hematochezia associated with hemodynamic instability may be indicative of an UGIB source, and an upper endoscopy should be performed. A nasogastric aspirate/lavage may be used to assess a possible upper GI source if suspicion of UGIB is moderate (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

3. Risk assessment and stratification should be performed to help distinguish patients at high and low risks of adverse outcomes and assist in patient triage including the timing of colonoscopy and the level of care (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Hemodynamic resuscitation

4. Patients with hemodynamic instability and/or suspected ongoing bleeding should receive intravenous fluid resuscitation with the goal of normalization of blood pressure and heart rate prior to endoscopic evaluation/intervention (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

5. Packed red blood cells should be transfused to maintain the hemoglobin above 7 g/dl. A threshold of 9 g/dl should be considered in patients with massive bleeding, significant comorbid illness (especially cardiovascular ischemia), or a possible delay in receiving therapeutic interventions (conditional recommendations, low-quality evidence).

Management of anticoagulant medications

6. Endoscopic hemostasis may be considered in patients with an INR of 1.5–2.5 before or concomitant with the administration of reversal agents. Reversal agents should be considered before endoscopy in patients with an INR >2.5 (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

7. Platelet transfusion should be considered to maintain a platelet count of 50 × 10/l in patients with severe bleeding and those requiring endoscopic hemostasis (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

8. Platelet and plasma transfusions should be considered in patients who receive massive red blood cell transfusions (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

9. In patients on anticoagulant agents, a multidisciplinary approach (e.g., hematology, cardiology, neurology, and gastroenterology) should be used when deciding whether to discontinue medications or use reversal agents to balance the risk of ongoing bleeding with the risk of thromboembolic events (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy as a diagnostic tool

10. Colonoscopy should be the initial diagnostic procedure for nearly all patients presenting with acute LGIB (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

11. The colonic mucosa should be carefully inspected during both colonoscope insertion and withdrawal, with aggressive attempts made to wash residual stool and blood in order to identify the bleeding site. The endoscopist should also intubate the terminal ileum to rule out proximal blood suggestive of a small bowel lesion (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Bowel preparation

12. Once the patient is hemodynamically stable, colonoscopy should be performed after adequate colon cleansing. Four to six liters of a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based solution or the equivalent should be administered over 3–4 h until the rectal effluent is clear of blood and stool. Unprepped colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy is not recommended (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

13. A nasogastric tube can be considered to facilitate colon preparation in high-risk patients with ongoing bleeding who are intolerant to oral intake and are at low risk of aspiration (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Timing of colonoscopy

14. In patients with high-risk clinical features and signs or symptoms of ongoing bleeding, a rapid bowel purge should be initiated following hemodynamic resuscitation and a colonoscopy performed within 24 h of patient presentation after adequate colon preparation to potentially improve diagnostic and therapeutic yield (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

15. In patients without high-risk clinical features or serious comorbid disease or those with high-risk clinical features without signs or symptoms of ongoing bleeding, colonoscopy should be performed next available after a colon purge (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Endoscopic hemostasis therapy

16. Endoscopic therapy should be provided to patients with high-risk endoscopic stigmata of bleeding: active bleeding (spurting and oozing); non-bleeding visible vessel; or adherent clot (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

17. Diverticular bleeding: through-the-scope endoscopic clips are recommended as clips may be safer in the colon than contact thermal therapy and are generally easier to perform than band ligation, particularly for right-sided colon lesions (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

18. Angioectasia bleeding: noncontact thermal therapy using argon plasma coagulation is recommended (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

19. Post-polypectomy bleeding: mechanical (clip) or contact thermal endotherapy, with or without the combined use of dilute epinephrine injection, is recommended (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

20. Epinephrine injection therapy (1:10,000 or 1:20,000 dilution with saline) can be used to gain initial control of an active bleeding lesion and improve visualization but should be used in combination with a second hemostasis modality including mechanical or contact thermal therapy to achieve definitive hemostasis (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Role of repeat colonoscopy in the setting of early recurrent bleeding

21. Repeat colonoscopy, with endoscopic hemostasis if indicated, should be considered for patients with evidence of recurrent bleeding (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Non-colonoscopy interventions

22. A surgical consultation should be requested in patients with high-risk clinical features and ongoing bleeding. In general, surgery for acute LGIB should be considered after other therapeutic options have failed and should take into consideration the extent and success of prior bleeding control measures, severity and source of bleeding, and the level of comorbid disease. It is important to very carefully localize the source of bleeding whenever possible before surgical resection to avoid continued or recurrent bleeding from an unresected culprit lesion (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

23. Radiographic interventions should be considered in patients with high-risk clinical features and ongoing bleeding who have a negative upper endoscopy and do not respond adequately to hemodynamic resuscitation efforts and are therefore unlikely to tolerate bowel preparation and urgent colonoscopy (strong recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

24. If a diagnostic test is desired for localization of the bleeding site before angiography, CT angiography should be considered (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Prevention of recurrent lower gastrointestinal bleeding

25. Non-aspirin NSAID use should be avoided in patients with a history of acute LGIB, particularly if secondary to diverticulosis or angioectasia (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

26. In patients with established high-risk cardiovascular disease and a history of LGIB, aspirin used for secondary prevention should not be discontinued. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events should be avoided in most patients with LGIB (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

27. In patients on dual antiplatelet therapy or monotherapy with non-aspirin antiplatelet agents (thienopyridine), non-aspirin antiplatelet therapy should be resumed as soon as possible and at least within 7 days based on multidisciplinary assessment of cardiovascular and GI risk and the adequacy of endoscopic therapy (as above, aspirin use should not be discontinued). However, dual antiplatelet therapy should not be discontinued in patients with an acute coronary syndrome within the past 90 days or coronary stenting within the past 30 days (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Algorithm for the management of patients presenting with acute LGIB stratified by bleeding severity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed