Introduction:

Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: the hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N). There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes. (H1 through H18 and N1 through N11 respectively.)

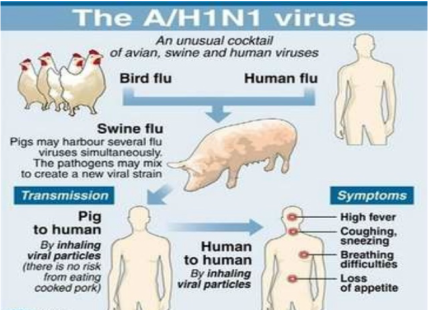

Influenza A viruses can be further broken down into different strains. Current subtypes of influenza A viruses found in people are influenza A (H1N1) and influenza A (H3N2) viruses. In the spring of 2009, a new influenza A (H1N1) virus (2009 H1N1 Flu) emerged to cause illness in people. This virus was very different from the human influenza A (H1N1) viruses circulating at that time. The new virus caused the first influenza pandemic in more than 40 years. That virus (often called “2009 H1N1”) has now replaced the H1N1 virus that was previously circulating in humans.

Influenza B viruses are not divided into subtypes, but can be further broken down into lineages and strains. Currently circulating influenza B viruses belong to one of two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria.

There is an internationally accepted naming convention for influenza viruses. This convention was accepted by WHO in 1979 and published in February 1980 in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58(4):585-591 (1980) . The approach uses the following components:

- The antigenic type (e.g., A, B, C)

- The host of origin (e.g., swine, equine, chicken, etc. For human-origin viruses, no host of origin designation is given.)

- Geographical origin (e.g., Denver, Taiwan, etc.)

- Strain number (e.g., 15, 7, etc.)

- Year of isolation (e.g., 57, 2009, etc.)

- For influenza A viruses, the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigen description in parentheses (e.g., (H1N1), (H5N1)

- A/duck/Alberta/35/76 (H1N1) for a virus from duck origin

- A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2) for a virus from human origin

Signs and symptoms:

Severe cases:

A November 2009 CDC recommendation stated that the following constitute "emergency warning signs" and advised seeking immediate care if a person experiences any one of these signs:

In adults:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Pain or pressure in the chest or abdomen

- Sudden dizziness

- Confusion

- Severe or persistent vomiting

- Low temperature

In children:

- Fast breathing or working hard to breathe

- Bluish skin color

- Not drinking enough fluids

- Not waking up or not interacting

- Being so irritable that the child does not want to be held

- Flu-like symptoms which improve but then return with fever and worse cough

- Fever with a rash

- Being unable to eat

- Having no tears when crying

Transmission:

The basic reproduction number (the average number of other individuals whom each infected individual will infect, in a population which has no immunity to the disease) for the 2009 novel H1N1 is estimated to be 1.75. A December 2009 study found that the transmissibility of the H1N1 influenza virus in households is lower than that seen in past pandemics. Most transmissions occur soon before or after the onset of symptoms.

The H1N1 virus has been transmitted to animals, including swine, turkeys, ferrets, household cats, at least one dog and a cheetah

Diagnosis:

How the Flu Virus Can Change: “Drift” and “Shift”

One way they change is called “antigenic drift.” These are small changes in the genes of influenza viruses that happen continually over time as the virus replicates. These small genetic changes usually produce viruses that are pretty closely related to one another, which can be illustrated by their location close together on a phylogenetic tree. Viruses that are closely related to each other usually share the same antigenic properties and an immune system exposed to an similar virus will usually recognize it and respond. (This is sometimes called cross-protection.)

But these small genetic changes can accumulate over time and result in viruses that are antigenically different (further away on the phylogenetic tree). When this happens, the body’s immune system may not recognize those viruses.

This process works as follows: a person infected with a particular flu virus develops antibody against that virus. As antigenic changes accumulate, the antibodies created against the older viruses no longer recognize the “newer” virus, and the person can get sick again. Genetic changes that result in a virus with different antigenic properties is the main reason why people can get the flu more than one time. This is also why the flu vaccine composition must be reviewed each year, and updated as needed to keep up with evolving viruses.

The other type of change is called “antigenic shift.” Antigenic shift is an abrupt, major change in the influenza A viruses, resulting in new hemagglutinin and/or new hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins in influenza viruses that infect humans. Shift results in a new influenza A subtype or a virus with a hemagglutinin or a hemagglutinin and neuraminidase combination that has emerged from an animal population that is so different from the same subtype in humans that most people do not have immunity to the new (e.g. novel) virus. Such a “shift” occurred in the spring of 2009, when an H1N1 virus with a new combination of genes emerged to infect people and quickly spread, causing a pandemic. When shift happens, most people have little or no protection against the new virus.

While influenza viruses are changing by antigenic drift all the time, antigenic shift happens only occasionally. Type A viruses undergo both kinds of changes; influenza type B viruses change only by the more gradual process of antigenic drift.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- en.wikipedia.org

RSS Feed

RSS Feed